The Great Context Engineering Debate: Does It Matter for PMs Without Agents?

There’s been a little intellectual tug-of-war in the Guru household this past week. It started when I was prepping my AI Product Foundations class and mentioned I was thinking of adding context engineering to the curriculum.

My husband’s response: “Why? Your students aren’t building agents.”

He had a point. But let me make this concrete before I explain why I disagreed.

The Product Decision That Started This

You’re a PM building an AI-powered customer support assistant. Your team is debating the architecture.

Option A: Build a RAG system with great context management. It retrieves relevant help articles, considers conversation history, and generates helpful responses.

Option B: Build a multi-step agent that can file support tickets, follow up with customers, check order status across systems, and summarize conversation threads.

Both can “help customers.” But they’re fundamentally different products with different trade-offs.

Option A is faster to build, more predictable and easier to debug. But it can only answer questions. It can’t take action.

Option B can actually do things on behalf of customers. But it’s more complex, harder to test, and introduces failure modes you’ve never dealt with before.

This is the decision context engineering helps you make. Not “should I use AI?” but “how much AI autonomy does this problem actually require?”

I’ll come back to this scenario at the end. Keep it in mind as we go.

What Is Context Engineering, Anyway?

For PMs, context engineering is about deciding what instructions, data, and history the model sees so it behaves as your product needs.

The term gained traction in mid-2025. Andrej Karpathy called it “the delicate art and science of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step.” Tobi Lütke (Shopify’s CEO) said he prefers “context engineering” over “prompt engineering” because it better describes what we’re actually doing: providing all the context for a task to be plausibly solvable by the LLM.

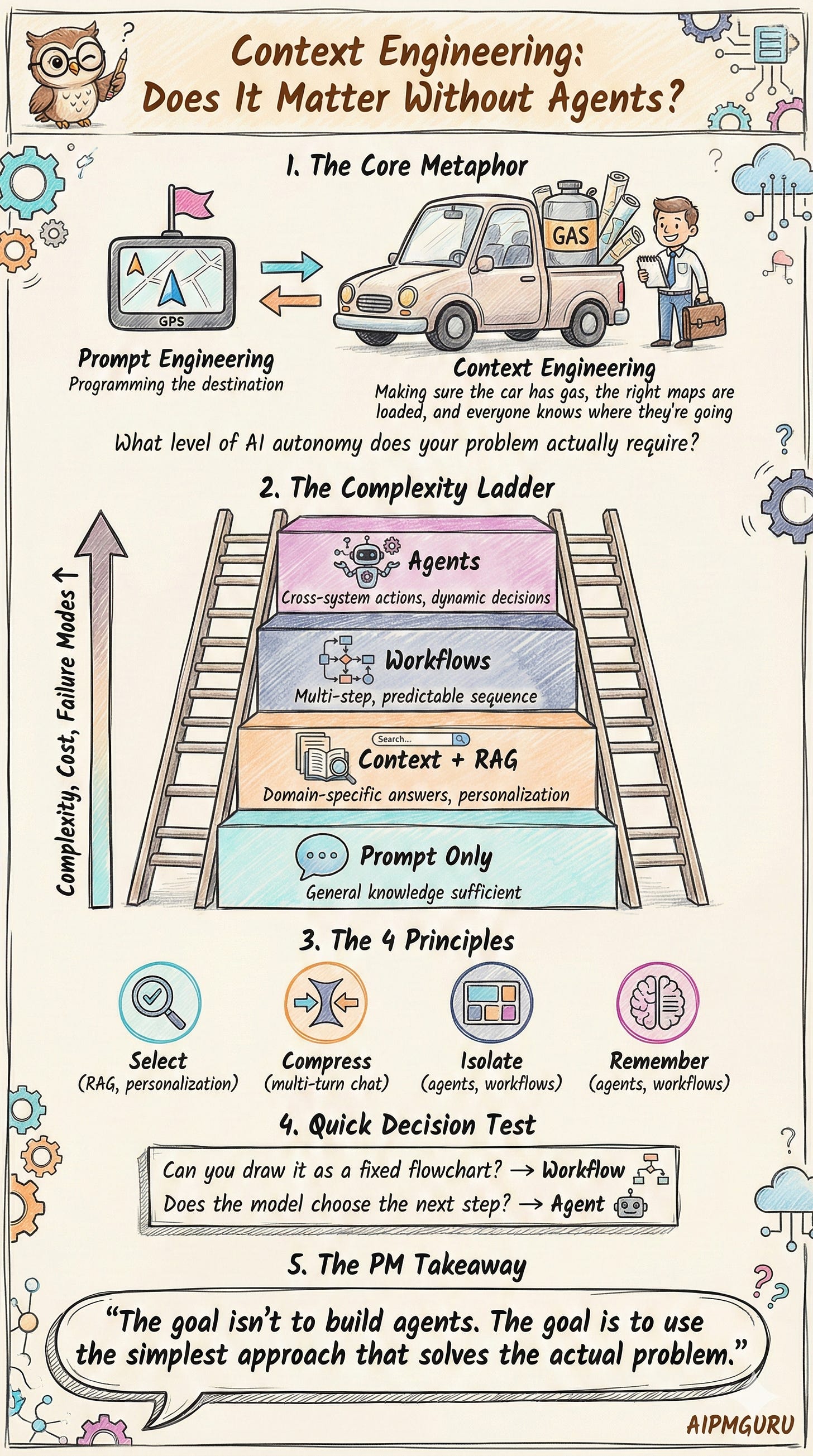

I’ve been explaining it to my students like this: prompt engineering is programming the GPS destination. Context engineering is making sure the car has gas, the right maps are loaded, and everyone knows where they’re going.

With prompt engineering, you’re focused on how you ask. The wording, the structure, the format you request.

With context engineering, you’re focused on what information the model sees when it processes your request. That includes your prompt, retrieved documents, conversation history, tool definitions, user data, and system instructions. Everything that lands in the context window.

A brilliant prompt can’t save you if the model’s working with the wrong information. And a simple prompt, supported by carefully curated context, can deliver surprisingly good results.

The Four Principles

The term “context engineering” was coined to describe agent-specific challenges. Anthropic’s definitive article is titled “Effective Context Engineering for AI Agents.”

But the principles underneath it show up across different application types. LangChain groups context engineering into four operations: write, select, compress, and isolate. Here’s what each one means and where PMs encounter them:

1. Selecting Context (RAG, personalization, knowledge retrieval)

Pulling the right information into the context window. Not everything that could be relevant. Just what’s needed for this specific task.

The most common example is RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation). Quick primer: RAG fetches relevant documents or data before generating a response. Instead of relying solely on training data, you provide the model with fresh, specific information.

Selection is the hard part. Which documents do you retrieve? How many? How do you rank them? These decisions directly impact output quality.

2. Compressing Context (multi-turn chat, long documents)

Retaining only the tokens required for the task. This might mean summarizing older conversation turns, extracting key facts from long documents, or truncating tool outputs.

The goal is to preserve the signal while reducing the noise. Too little context and the model lacks information. Too much and you waste tokens, increase latency, and potentially degrade performance.

I think of it like packing for a trip. Take too little and you’re unprepared. Take too much and you can’t move.

3. Isolating Context (mostly agents and advanced workflows)

Splitting context to prevent interference or manage scope. A research agent and a writing agent might need different tools, different instructions, and different memories. Isolation keeps them from stepping on each other.

For simpler applications, isolation is less relevant. It becomes critical when coordinating multiple LLM calls with different purposes.

4. Writing Context / Memory (mostly agents and advanced workflows)

Saving information outside the context window for later retrieval. Short-term memory might be a scratchpad for intermediate findings. Long-term memory might be user preferences that persist across sessions.

This is what lets an agent say “I looked into this earlier” without keeping the entire investigation in the active context window.

My Husband’s Case: Why It’s Fundamentally an Agent Problem

Over dinner, my husband laid out his argument. It’s solid.

Agents face challenges that simpler applications don’t have.

Context accumulates unpredictably. An agent running a 50-step task gathers tool results, intermediate reasoning, and error messages. The Manus team reports 100:1 input-to-output token ratios. That’s a lot of context piling up.

The context window changes mid-task. A chatbot rebuilds context each turn. An agent maintains a running state across many LLM calls. This creates “context rot,” where performance degrades as the window fills with stale information.

Tool results inject unpredictable content. When an agent calls an API, you don’t control what comes back. A web search might return garbage. That content lands in your context window regardless.

His point: these problems require all four principles working together. If you’re not dealing with them, you’re doing prompt design with retrieval, not context engineering.

I see where he’s coming from.

My Case: Why the Principles Still Matter for Foundations

But my students aren’t building agents first. They’re building chatbots. RAG applications. Workflow automations. And those still need context management.

Multi-turn conversations hit context limits. Even a basic chatbot eventually fills its window. Do you truncate older messages? Summarize them? That’s selection and compression.

RAG is context engineering by another name. Every retrieval system makes decisions about what to fetch, how to rank it, and how to fit it alongside the query.

Personalization requires context curation. If your product uses user preferences or history, you’re deciding what context to include.

My argument: even if students don’t need all four principles yet, they need to understand that context is a resource to be managed. That’s foundational.

The Decision Framework: How Much Complexity Do You Actually Need?

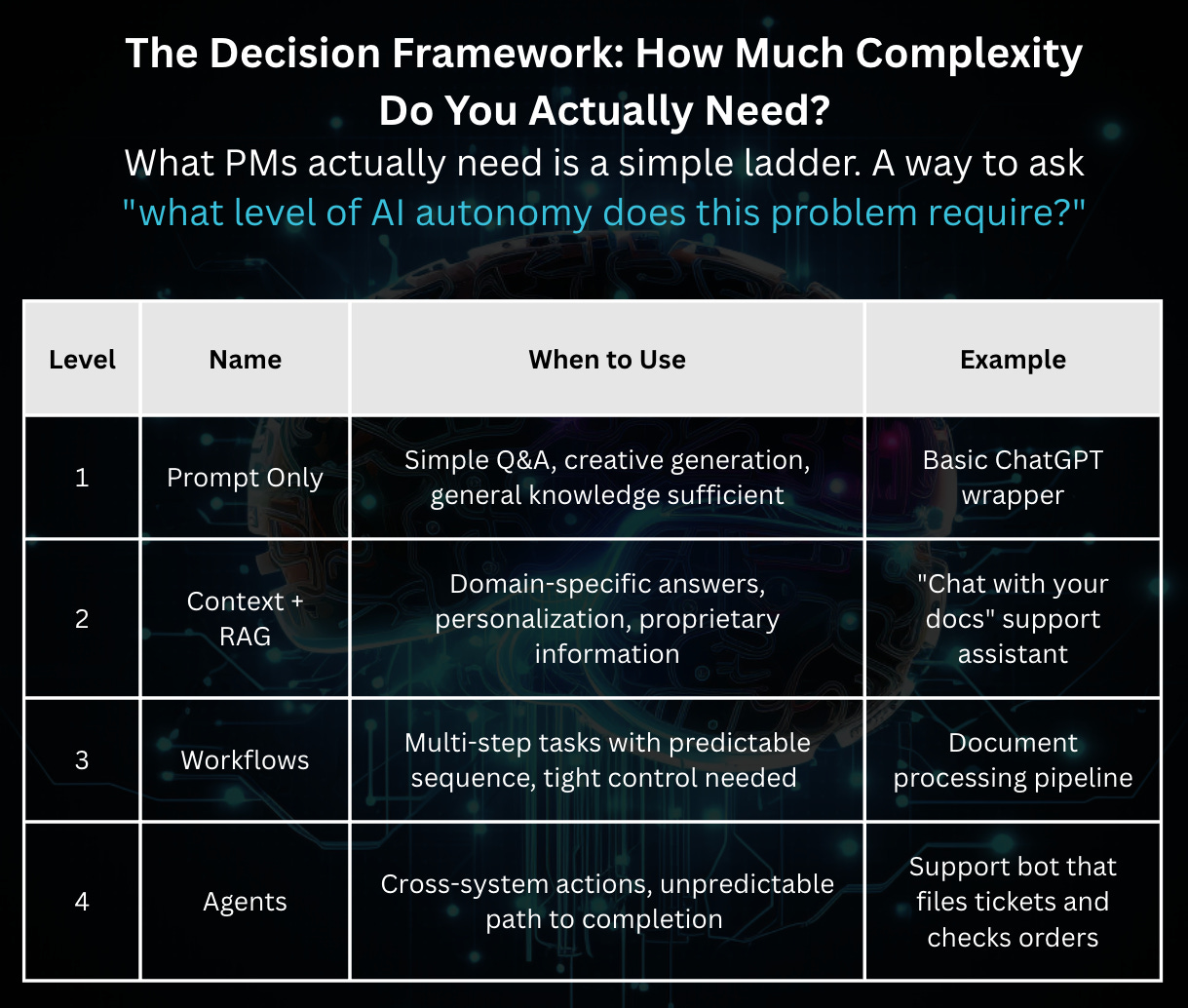

What PMs actually need is a simple ladder. A way to ask “what level of AI autonomy does this problem require?”

The test for Level 3 vs Level 4: If you can draw the flow as a fixed BPMN-style diagram, it’s a workflow. If the model needs to choose the next step based on what it discovers, you’re in agent territory.

Each level adds capability but also complexity, cost, and failure modes. The goal isn’t to build agents. The goal is to use the simplest approach that solves the actual problem.

What PMs Actually Own in Context Engineering

Context engineering isn’t just a model-side concern. PMs make context decisions constantly, even if they don’t call it that.

Choosing data sources. What knowledge bases, documents, or APIs should the system draw from? For the support bot: only docs tagged “public” and “current,” not internal engineering specs.

Shaping instructions. The system prompt is context. How you frame the task, what constraints you set, and what persona you define. For the support bot: “You are a helpful support agent. Never discuss pricing or make promises about refunds.”

Defining constraints and guardrails. What topics should the AI refuse? What actions require human approval? For the support bot: escalate to human if customer mentions “lawyer” or “lawsuit.”

Deciding what history to keep or drop. In a multi-turn conversation, what matters? For the support bot: always retain the original issue description, summarize troubleshooting steps after 5 turns.

Prioritizing retrieval quality. When RAG returns mediocre results, that’s a product problem. For the support bot: invest in better article tagging before adding agent capabilities.

The Context Brief: A PRD Artifact

One thing I think would strengthen any AI feature PRD: a “Context Brief.” It’s a one-pager that enumerates:

Instructions: System prompt, persona, constraints

Knowledge sources: Documents, APIs, databases the model accesses

History policy: How much conversation history? Summarized or verbatim?

Guardrails: Topics or actions that are off-limits

Retrieval requirements: How many documents? What relevance threshold?

This makes context a first-class product concern, not an afterthought that engineers figure out.

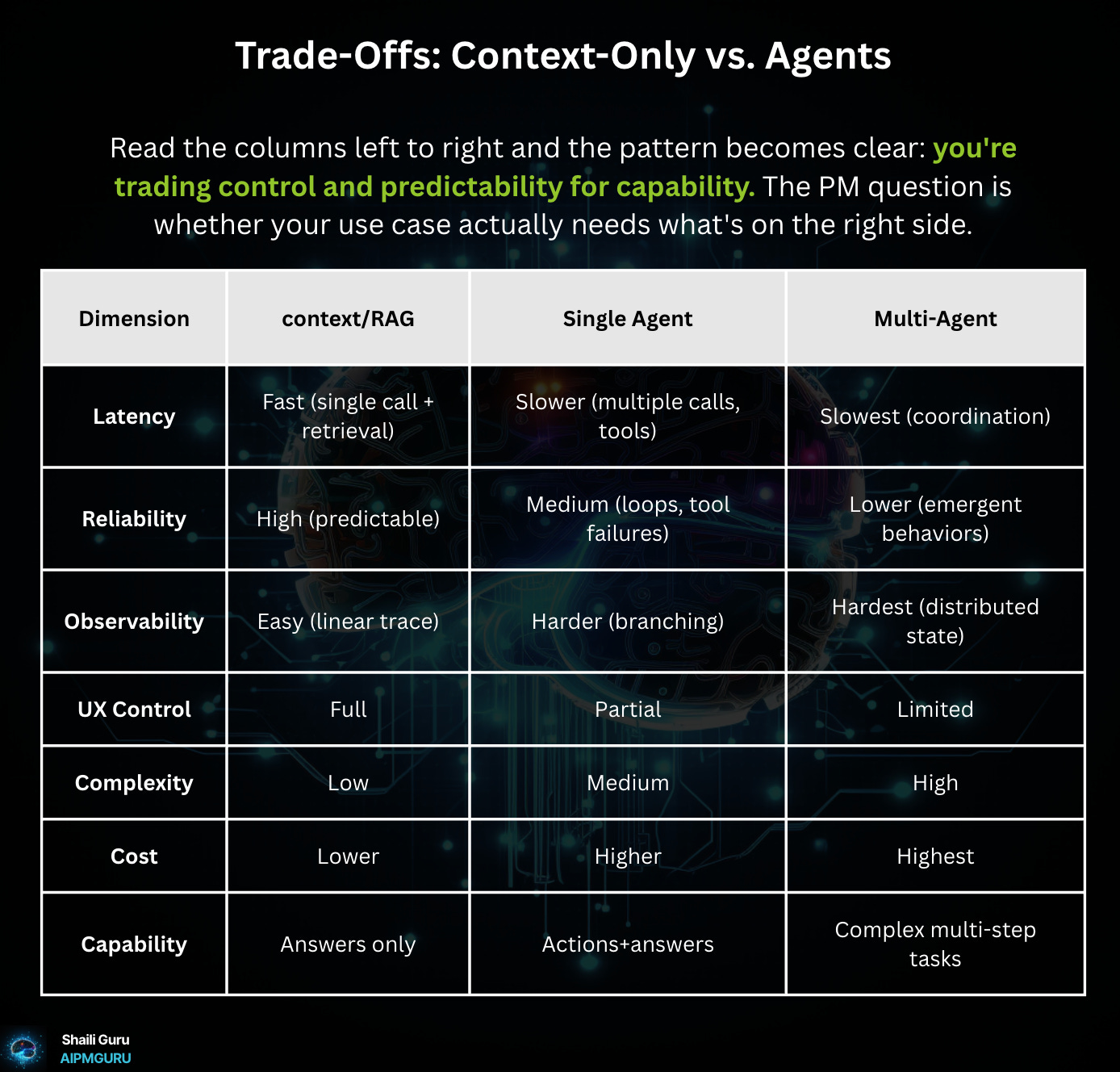

Trade-Offs: Context-Only vs. Agents

Here’s where it gets concrete about PM trade-offs.

Read the columns left to right and the pattern is clear: you’re trading control and predictability for capability. The PM question is whether your use case actually needs what’s on the right side.

Failure Modes to Watch

Context/RAG failures:

Retrieval gaps: relevant document exists but wasn’t retrieved

Context pollution: irrelevant information confuses the model

Agent failures:

Infinite loops: agent keeps trying the same failing approach

Tool misuse: wrong API called or bad parameters passed

Cascading errors: early mistake compounds through subsequent steps

Understanding failure modes helps you choose architecture. If you can’t tolerate infinite loops in customer-facing support, maybe agents aren’t the right call yet.

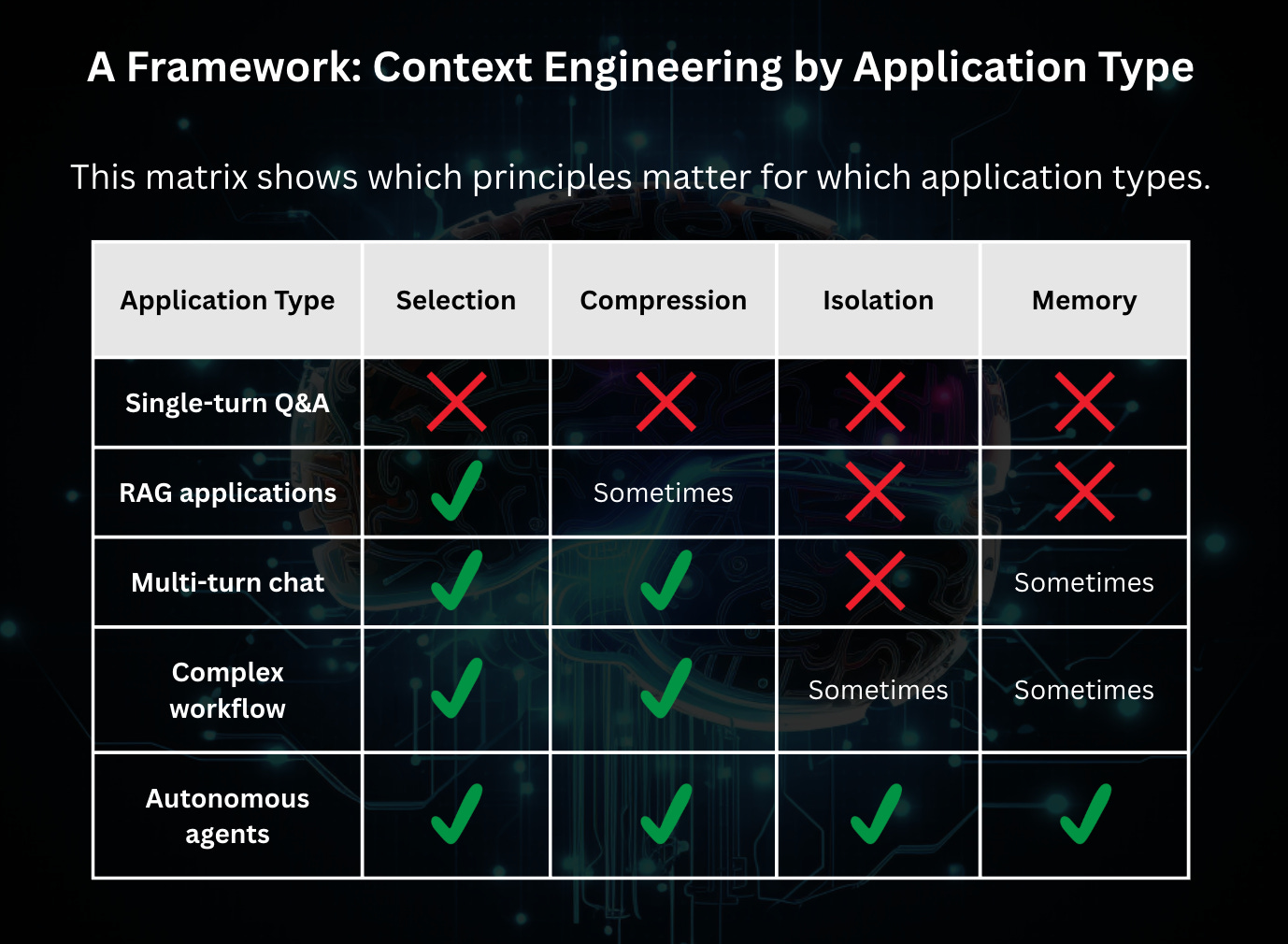

A Framework: Context Engineering by Application Type

This matrix shows which principles matter for which application types.

Legend:

✅ = primary concern for this application type.

Sometimes = becomes important beyond simple MVP, or for specific use cases.

The more complex your application, the more principles you need. Agents need all four. Simpler applications need fewer. But fewer isn’t none.

Where I Landed on the Curriculum

Am I teaching context engineering in AI Product Foundations?

Yes. But scoped appropriately.

I’ll introduce the concept and explain why context is a resource to be managed. We’ll cover selection (because everyone encounters RAG) and compression (because everyone builds something with conversation history).

Isolation and memory can wait for an advanced module on agents. My foundations students don’t need multi-agent coordination yet.

But I want them thinking about context from day one. When they eventually build agents (or inherit an agent codebase, or evaluate an agent product) they’ll have the mental model to understand what’s happening.

My husband still thinks I’m overcomplicating it. But he admitted the framework table was useful.

We agreed to disagree.

Back to the Support Assistant

Remember the opening scenario?

Option A (RAG with great context): Retrieve help articles, consider conversation history, generate responses. Invest in retrieval quality and context management. The assistant answers questions well but can’t take action.

Option B (Multi-step agent): File tickets, look up orders, follow up with customers. More capable, but more complex.

Here’s how I’d think through it now:

If 80% of support queries are “how do I do X?” questions that your help docs already answer, Option A might be right. You’re solving the actual problem with less complexity. Invest in great context engineering, ship faster, fail less often, and run at lower cost.

If customers constantly need actions (”cancel my order,” “change my address”), Option A will frustrate them. You need Option B and must accept the complexity.

The context engineering framing helps you see this isn’t “dumb chatbot vs. smart agent.” It’s “what level of autonomy does this problem require?” That’s a product decision.

How to Use This in Interviews and On the Job

Understanding context engineering makes you a more credible AI PM.

In interviews:

When asked “How would you approach building an AI feature?” don’t jump to “we’d use GPT-4.” Walk through the ladder:

“First, I’d assess what level of AI autonomy this problem requires.”

“If it’s information retrieval, I’d start with RAG and invest in context quality.”

“If it requires cross-system actions, we’d consider agents, but I’d want to understand reliability and observability trade-offs first.”

If an interviewer asks, “How would you improve this AI feature?” use the ladder to propose a context-only improvement before suggesting agents. That shows you understand complexity trade-offs.

Prompts to practice:

“Walk me through how you’d decide between RAG and agents for a customer support product.”

“How would context window limitations affect your product design?”

“What would you include in a PRD for an AI feature?”

On the job:

Context engineering gives you vocabulary for engineering conversations. Instead of “make the AI smarter,” you can say “I think we have a retrieval quality problem” or “we should summarize conversation history after 10 turns.”

It also helps you push back on complexity. When someone proposes agents, ask: “What problem does the agent solve that we can’t solve with better context?”

Sometimes the answer is “nothing, actually.” Knowing when not to build the complex thing is a PM superpower.

What’s Next

If you’re building AI products, think about where your application falls on that complexity ladder. You probably don’t need agents. But you probably need better context management than you have.

One concrete action: Try writing a Context Brief for a feature you already own. Even a rough draft will surface decisions you’ve been making implicitly.

If you’re teaching this stuff or onboarding new team members, I’d love to hear where you draw the line. Is context engineering strictly an agent problem? Or does it belong in foundational AI education?

Drop a comment. I’m genuinely curious how others are thinking about this.

Sources

Glossary

Single-turn Q&A: One-shot interaction without retrieval, history, or external data. The context window contains only system prompt and user message.

RAG applications: Retrieval-Augmented Generation systems that fetch documents or data before responding. Examples: “chat with your docs,” support bots with knowledge bases.

Multi-turn chat: A conversation with multiple back-and-forth exchanges where the AI needs to remember what was said earlier. Each “turn” is one exchange (user message + AI response). In a multi-turn chat, the AI must keep track of previous turns to give coherent responses. Example: if you tell the AI you’re planning a trip to France in turn 1, it should remember that context when you ask “what should I pack?” in turn 5.

Older conversation turns: The earlier messages in a long conversation. When a chat goes on for 20, 30, 50+ turns, context window limits force decisions about which earlier turns to keep, summarize, or drop.

Complex workflows: Orchestrated multi-step LLM calls with deterministic (code-defined) control flow. The sequence is predefined, unlike agents.

Autonomous agents: Systems where the LLM decides what actions to take and when the task is complete. The model operates in a reasoning-acting-observing loop until it achieves a goal.

BPMN (Business Process Model and Notation): A standardized visual language for mapping business workflows as flowcharts, using specific shapes for tasks, decisions, and flow. If you’ve ever drawn a process diagram with decision diamonds and swim lanes, you’ve used BPMN concepts.

Retrieval gaps: The relevant document exists in your knowledge base, but the system didn’t surface it. Maybe the user’s query used different terminology than the document, or the embedding similarity score fell below your threshold. The user gets a generic answer when a specific one is available. This is one of the most common RAG failures because the information was right there.

Context pollution: The retrieval worked, but it pulled in irrelevant or partially relevant information alongside the good stuff. The model treats everything in its context window as potentially important, so noisy results can confuse the response. Example: a user asks about your return policy, and the retrieval also pulls in an internal HR document about employee returns from leave.

Infinite loops: The agent tries an approach, it fails, and it tries the same approach again (or a nearly identical variation). Without proper exit conditions, it burns through tokens and time while the user waits. Especially problematic in customer-facing products where users can see the agent spinning.

Tool misuse: The agent picks the wrong tool for the task, or calls the right tool with bad parameters. Example: an agent meant to look up order status instead calls the “cancel order” API because the function names were similar. This is why tool descriptions and guardrails matter so much in agent design.

Cascading errors: An early mistake propagates through the agent’s subsequent steps. The agent misinterprets step 1, uses that wrong output as input for step 2, and by step 5 the results are completely off track. Debugging is hard because the root cause is several steps back from where the visible problem appears.

Great post! The question of complexity is really key. I’ve noticed that many PMs are pushed toward implementing complex AI solutions, even when a simpler approach could work. I’m not just thinking about final products, but also early-stage developments or even PoCs, which can benefit greatly from lower-complexity solutions. Context, engineering knowledge, and AI literacy also make a big difference! I’ve had conversations with stakeholders advocating for more complex approaches that required careful convincing.

Brilliant breakdown on the complexity ladder! The framing around "how much autonomy does this problem need" is exactly the right question. I've seen too many teams jump straight to agentic solutions when a well-tuned RAG system woudl have been faster and more reliable. The Context Brief idea is solid too, kinda like having a mini-spec for what the model actually "sees" at runtime.